I read 100 books in 2006. That’s fewer than last year, but in the same ballpark.

Those 100 books break down into 85 fiction titles, 13 non-fiction titles, and 2 collections of poetry. I always read more fiction than non-fiction but the numbers don’t usually tilt quite so decisively in favour of fiction. I’m not sure what to make of that. I suspect it’s an aberration. I’m early in the research phase of a couple of new projects at the moment and I have no doubt that the reading I do in connection with them will substantially raise the proportion of non-fiction in next year’s tally.

Of the 85 fiction titles, 73 were novels and 12 were short story collections. I would classify them as follows: 47 literary fiction, 27 mysteries, and 11 children’s or YA novels.

The non-fiction titles included biographies, memoirs, essays, and books on reading, writing, money, and health.

Eleven were rereads.

Twenty-five of the 100 were published by small or independent presses, and 75 by large, mainstream presses.

Sixty-one were written by women, and 39 by men.

Roughly one-third of the 100 were written by Canadian authors, one-quarter by U.S. authors, and most of the rest by UK authors.

Only one was a work in translation, a Quebec novel originally written in French and translated into English.

Only two pre-date the 20th century.

If all of the individual stories and essays that I read in addition to these books were taken into account, the diversity of my list in terms of countries of origin, works in translation, and time periods would improve. But significant gaps in my reading are obvious nonetheless. In light of this, you can anticipate what some of my reading resolutions for 2007 are likely to be.

Speaking of reading resolutions, I made a slate of them for 2006 and now is the time to assess how I fared. On the whole, I fared rather well. It seems that I’m much better at keeping reading resolutions than any other kind. The reason for this is readily apparent. Reading resolutions don’t represent attempts to pressure myself into doing things that I don’t want to do. Rather, they constitute permissions to myself to give priority to things that I do want to do but that might otherwise get lost amidst the stresses of daily life. Perhaps I ought to extend this resolution philosophy into other areas of my life...

On to the specifics…

My first resolution was to read the work alongside the biographies. I only read two literary biographies this year: Claire Harman’s excellent biography of Robert Louis Stevenson, and David Callard’s serviceable biography of Anna Kavan. In each instance I read several works by the subject either alongside the biography or shortly after finishing it. This practice definitely gave added depth to the insights that the biographies offered into the work and creative processes of the subjects and I plan to continue it.

My second was to revisit the work of some of the writers in my pantheon of greats. I reread a number of novels and stories by Anton Chekhov, Jean Rhys, Muriel Spark, Jean Stafford, and Adele Wiseman and relished the experience.

My third was to read some Samuel Beckett in honour of the centenary of his birth. I failed miserably at this one. For $1 at a library book sale I bought a Grove Press edition that contains three of his novels in a single paperback volume: Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable. I have carried this volume around with me for ages and have so far only made it to page 11 of Malloy. Perhaps I would do better with three separate volumes with bigger print. I will definitely give Beckett another go in 2007.

My fourth was to search out small press titles from outside Canada. I did quite well at searching them out but not so well at actually reading them. Nevertheless a tantalizing array of small press titles from the U.S. and the UK now form part of my TBR stack and I look forward to reading them in due course.

My fifth was to devote more blog space to discussion of Canadian small press books. A quick tally reveals that I have mentioned 49 Canadian small press titles, some of them more than once, in blog entries over the course of 2006. Some were just passing mentions in connection with notices of or reports on public readings, but several involved full reviews or links to reviews published elsewhere. I will definitely continue to bring worthy Canadian small press titles to the attention of fellow readers at every opportunity.

Finally, my sixth was to turn more often to the books that languish unread in my own collection rather than always rushing off to the library in search of something new. Fifty-seven of my 100 books read were checked out from the library whereas 43 were from my own collection. This is a substantial improvement over last year. Mind you, I’ve bought many more books as well, so there are still an ample number of unread books on my shelves awaiting my attention.

Stay tuned for posts outlining my reading resolutions for 2007 and my ten favourite reads from 2006.

Sunday, December 31, 2006

The Thirteenth Tale

Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale begins with a letter. Arriving home to the flat above her father’s bookshop on a dark November afternoon, biographer Margaret Lea finds a missive from author Vida Winter awaiting her. Winter is “England’s best-loved author,” a prolific writer who has had 56 books published in 56 years, and who is “as famous for her secrets as for her stories.” She has given interview after interview over the years and has blithely lied through all of them. Many a biographer has tried and failed to uncover the truth of her life. Now Winter is apparently ready to tell that truth and she has chosen Margaret to tell it to.

This seems a perfect set-up to pique my interest but in fact I wasn’t immediately drawn in. At first I found Margaret’s voice oddly stilted, archaic even. I didn’t find it a convincing voice for a contemporary character. Fortunately the bookish lore connected with her father’s antiquarian book business kept me turning the pages thereby giving Margaret a chance to win me over. Ultimately it was revelations about her reading preferences that made her voice begin to ring true and her motivations become comprehensible to me. She’s stuck in the past. She is more comfortable with dead writers than with living ones. She doesn’t read contemporary fiction at all:

I read old novels. The reason is simple: I prefer proper endings. Marriages and deaths, noble sacrifices and miraculous restorations, tragic separations and unhoped-for reunions, great falls and dreams fulfilled; these in my view, constitute an ending worth the wait. They should come after adventures, perils, dangers and dilemmas, and wind everything up nice and neatly. Endings like this are to be found more commonly in old novels than new ones, so I read old novels.

Before Vida Winter’s letter arrived, Margaret hadn’t read a single one of her 56 books. As it turns out, however, Miss Winter shares her aesthetic. She writes exactly the sort of books that Margaret loves to read. Miss Winter explains the secret of her success to Margaret thus:

‘Do you know why my books are so successful?’

‘For a great many reasons, I believe.’

‘Possibly. Largely it is because they have a beginning, a middle, and an end. In the right order. Of course all stories have beginnings, middles and endings; it is having them in the right order that matters. That is why people like my books.’

Margaret is seduced by Miss Winter’s stories and ultimately persuaded to accept a commission to serve as her biographer. Miss Winter accedes to Margaret’s initial request that she provide independently verifiable answers to three questions to build trust between them. But thereafter she insists on telling her story her own way:

‘After this, no more jumping about in the story. From tomorrow, I will tell you my story, beginning at the beginning, continuing with the middle, and with the end at the end. Everything in its proper place. No cheating. No looking ahead. No questions. No sneaky glances at the last page.’

It is at around page 60 when Miss Winter begins to tell her tale in earnest that the novel really takes off. It’s a fantastic gothic tale complete with cruelty, incest, arson, mysterious governesses, ghosts, and crumbling mansions. Improbable twist heaps upon improbable twist. But the reader is well prepared by all that’s gone before for just this sort of story, and for the possibility that Miss Winter is not being altogether honest in the telling of it. Again and again Miss Winter draws attention to the constructedness of her tale, from her initial insistence on the proper order of things, telling it her way, through to pronouncements like that which closes the following exchange:

I emerged from the spell of the story and into Miss Winter’s glazed and mirrored library.

‘Where did she go?’ I wondered.

Miss Winter eyed me with a slight frown. ‘I’ve no idea. What does it matter?’

‘She must have gone somewhere.’

The storyteller gave me a sideways look. ‘Miss Lea, it doesn’t do to get attached to these secondary characters. It’s not their story. They come, they go, and when they go they’re gone for good. That’s all there is to it.’

Margaret, although the primary narrator, is something of a secondary character in the novel as a whole. The reader gets just enough of her story to understand why she’s willing to play the role that she does. For my part I never developed much interest in Margaret’s story. But I did become very interested in Margaret’s reception of Miss Winter’s story, in the way her mind worked, in the kind of questions that she asked. These questions are in part those of a biographer. But it is underscored right from the beginning that Margaret is “not a proper biographer,” that she’s “hardly a biographer at all” but rather “a talented amateur.” Her role here is really that of reader rather than biographer, and this is why The Thirteenth Tale is ultimately such a reader’s book.

Margaret puzzles over Miss Winter’s tale, trying to make the connections, trying to get to the bottom of the story, but also trying to understand the author’s choices in the telling of the tale:

The twins themselves puzzled me. I knew what other people thought of them. John-the-dig thought they couldn’t speak properly; the Missus believed they didn’t understand other people were alive; the villagers thought they were wrong in the head. What I didn’t know—and this was more than curious—was what the storyteller thought. In telling her tale, Miss Winter was like the light that illuminates everything but itself. She was the disappearing point at the heart of the narrative. She spoke of they, more recently she had spoken of we; the absence that perplexed me was I.

The reader puzzles along with her.

On the face of it, The Thirteenth Tale is a glorious old-fashioned novel. But at the same time, it’s a meditation on the writing and the reading of glorious old-fashioned novels. I was riveted by the story at its centre, but also fascinated by the telling and the reception of it, by Miss Winter as author, and Margaret as reader. All this wrapped together makes for a deeply satisfying read.

Friday, December 29, 2006

Calvino Meme

When I asked in a recent post about novels written in the second person, Litlove mentioned Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler. This is a book that I bought ages ago but hadn’t yet cracked open. I pulled it down off the shelf today and am completely drawn in after only a few pages. I’ve decided to give it the fifth heretofore undecided slot in the list of books I plan to read before the end of January to meet the From the Stacks Challenge. I can’t resist a book with marvellous passages like the following which details the process by which “you,” the reader, made it out of the bookshop with the book you hold in your hands:

It occurred to me as I reached the end of this paragraph that Calvino’s list of bookshop temptations would make a fine meme. So I’m dubbing it the Calvino Meme and inviting anyone who wishes to participate to join in. Since he speaks of books, plural, let’s say that at least two books should be listed within each category, more if you like. Here goes:

Books You’ve Been Planning To Read For Ages:

I could list hundreds of books here but I’ll stop at three: A.S. Byatt’s Possession, Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe, and Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

Books You’ve Been Hunting For Years Without Success:

Since the advent of ebay and online second hand book vendors, there aren’t many of these on my list. But I’d still dearly love to find affordable hardback copies of the original editions of Maud Hart Lovelace’s Carney’s House Party and Emily of Deep Valley.

Books Dealing With Something You’re Working On At The Moment:

Mark Satin’s Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada and Henry Mietkiewicz’s Dream Tower: The Life and Legacy of Rochdale College. Both of these relate to my novel-in-progress which is partly set in Toronto in the late sixties and early seventies.

Books You Want To Own So They’ll Be Handy Just In Case:

Rob Colter’s Grammar to Go: A Portable A-Zed Guide to Canadian Usage and Malcolm MacLennan’s Gaelic Dictionary.

Books You Could Put Aside Maybe To Read This Summer:

There are a couple of big fat books that I’ve been meaning to read that might be best saved for the summer when I have a bit more time to spare: Mary Cosh’s Edinburgh: The Golden Age and The Complete Stories (in four volumes) of Morley Callaghan.

Books You Need To Go With Other Books On Your Shelves:

Volumes 3 and 4 of Virginia Woolf’s diaries, to complete my collection.

Books That Fill You With Sudden, Inexplicable Curiosity, Not Easily Justified:

I generally find it easy to justify my curiosity about any book. But here are a few on topics that I didn’t realize I was interested in until I picked them up: Karen Dubinsky’s The Second Greatest Disappointment: Honeymooning and Tourism at Niagara Falls, Timothy Ferris’s Coming of Age in the Milky Way and Gamini Salgado’s The Elizabethan Underworld.

Who else wants to play? Feel free to tack on any of the other categories of books Calvino enumerates in the passage I've quoted above. For example, is there anyone out there bold enough to list a title or two under the heading “Books You’ve Always Pretended To Have Read And Now It’s Time To Sit Down And Really Read Them”?

In the shop window you have promptly identified the cover with the title you were looking for. Following this visual trail, you have forced your way through the shop past the thick barricade of Books You Haven’t Read, which were frowning at you from the tables and shelves, trying to cow you. But you know you must never allow yourself to be awed, that among them there extend for acres and acres the Books You Needn’t Read, the Books Made For Purposes Other Than Reading, Books Read Even Before You Open Them Since They Belong To The Category Of Books Read Before Being Written. And thus you pass the outer girdle of ramparts, but then you are attacked by the infantry of the Books That If You Had More Than One Life You Would Certainly Also Read But Unfortunately Your Days Are Numbered. With a rapid maneuver you bypass them and move into the phalanxes of the Books You Mean To Read But There Are Others You Must Read First, the Books Too Expensive Now And You’ll Wait Till They’re Remaindered, the Books ditto When They Come Out In Paperback, Books You Can Borrow From Somebody, Books That Everybody’s Read So It’s As If You Had Read Them, Too. Eluding these assaults, you come up beneath the towers of the fortress, where other troops are holding out:

the Books You’ve Been Planning To Read For Ages,

the Books You’ve Been Hunting For Years Without Success,

the Books Dealing With Something You’re Working On At The Moment,

the Books You Want To Own So They’ll Be Handy Just In Case,

the Books You Could Put Aside Maybe To Read This Summer,

the Books You Need To Go With Other Books On Your Shelves,

the Books That Fill You With Sudden, Inexplicable Curiosity, Not Easily Justified.

Now you have been able to reduce the countless embattled troops to an array that is, to be sure, very large but still calculable in a finite number; but this relative relief is then undermined by the ambush of the Books Read Long Ago Which It’s Now Time To Reread and the Books You’ve Always Pretended To Have Read And Now It’s Time To Sit Down And Really Read Them.

It occurred to me as I reached the end of this paragraph that Calvino’s list of bookshop temptations would make a fine meme. So I’m dubbing it the Calvino Meme and inviting anyone who wishes to participate to join in. Since he speaks of books, plural, let’s say that at least two books should be listed within each category, more if you like. Here goes:

Books You’ve Been Planning To Read For Ages:

I could list hundreds of books here but I’ll stop at three: A.S. Byatt’s Possession, Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe, and Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

Books You’ve Been Hunting For Years Without Success:

Since the advent of ebay and online second hand book vendors, there aren’t many of these on my list. But I’d still dearly love to find affordable hardback copies of the original editions of Maud Hart Lovelace’s Carney’s House Party and Emily of Deep Valley.

Books Dealing With Something You’re Working On At The Moment:

Mark Satin’s Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada and Henry Mietkiewicz’s Dream Tower: The Life and Legacy of Rochdale College. Both of these relate to my novel-in-progress which is partly set in Toronto in the late sixties and early seventies.

Books You Want To Own So They’ll Be Handy Just In Case:

Rob Colter’s Grammar to Go: A Portable A-Zed Guide to Canadian Usage and Malcolm MacLennan’s Gaelic Dictionary.

Books You Could Put Aside Maybe To Read This Summer:

There are a couple of big fat books that I’ve been meaning to read that might be best saved for the summer when I have a bit more time to spare: Mary Cosh’s Edinburgh: The Golden Age and The Complete Stories (in four volumes) of Morley Callaghan.

Books You Need To Go With Other Books On Your Shelves:

Volumes 3 and 4 of Virginia Woolf’s diaries, to complete my collection.

Books That Fill You With Sudden, Inexplicable Curiosity, Not Easily Justified:

I generally find it easy to justify my curiosity about any book. But here are a few on topics that I didn’t realize I was interested in until I picked them up: Karen Dubinsky’s The Second Greatest Disappointment: Honeymooning and Tourism at Niagara Falls, Timothy Ferris’s Coming of Age in the Milky Way and Gamini Salgado’s The Elizabethan Underworld.

Who else wants to play? Feel free to tack on any of the other categories of books Calvino enumerates in the passage I've quoted above. For example, is there anyone out there bold enough to list a title or two under the heading “Books You’ve Always Pretended To Have Read And Now It’s Time To Sit Down And Really Read Them”?

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

By the Transport of Books

I missed my studies with Dr. Trefusis inveterately; for reading, once begun, quickly becomes home and circle and court and family; and indeed, without narrative, I felt exiled from my own country. By the transport of books, that which is most foreign becomes one's familiar walks and avenues; while that which is most familiar is removed to delightful strangeness; and unmoving, one travels infinite causeways; immobile and thus unfettered.

From M. T. Anderson, The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing: Traitor to the Nation, Volume I - The Pox Party.

Friday, December 22, 2006

Surreptitious Holiday Reading

I'm back in my hometown to spend Christmas with my family. I've had only sporadic internet access since I arrived which accounts for the recent dearth of posts here. I've been doing plenty of reading though, zigzagging my way through a bewildering array of books. You see, I've been frantically attempting to finish all the books that I'm gifting to friends and family before handing them over on the 25th. Thus what I'm reading when depends entirely on who happens to be wandering about the house at the time. Does anyone else engage in such surreptitious holiday reading? Or do you feel that books that you give as gifts ought to be handed over in pristine, never-been-opened condition? I'm rather shameless about it, the surreptitiousness having to do with not wanting people to know in advance what book they're getting, not with concealing my pre-reading of them. After all, it's common practice in my family. I'm quite sure that even as I'm reading their books, other members of my family are busily reading the ones that they've bought for me. Besides, I feel honour bound to have read the books I gift in advance to make sure that they are indeed good ones that I'm quite sure the intended recipient will enjoy.

I promise a full report once I'm back at my own computer on who gave who what book and how they went over...

I promise a full report once I'm back at my own computer on who gave who what book and how they went over...

Saturday, December 16, 2006

Wriggling Through By Subtle Manoeuvres

Franz Kafka on finding time to write:

From Franz Kafka,”Letter to His Father”; cited in Ruth V. Gross, “Kafka’s Short Fiction” in Julian Preece, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Kafka (2002).

My mode of life is devised solely for writing, and if there are any changes, then only for the sake of perhaps fitting in better with my writing; for time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle manoeuvres. The satisfaction gained by manoeuvring one’s timetable successfully cannot be compared to the permanent misery of knowing that fatigue of any kind shows itself better and more clearly in writing than anything one is really trying to say.

From Franz Kafka,”Letter to His Father”; cited in Ruth V. Gross, “Kafka’s Short Fiction” in Julian Preece, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Kafka (2002).

Friday, December 15, 2006

Reading Like a Writer

I suspected that I was going to like Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer based on the title alone. I’m a firm believer in reading as a means to improve writing, and I’ve said here before that my primary motivation for beginning this blog was to compel myself to read more rigorously, to take the time necessary to puzzle over what does and doesn’t work in the books that I read.

I’m only a chapter into Prose’s book and it’s already amply living up to my expectations. Here’s a passage that I identify with completely on what it means to her to read like a writer :

I also read with interest what Prose had to say about fearing the influence of other writers:

I do worry about the influences that I expose myself to while I’m at the initial drafting stage of a piece of fiction. I don’t avoid reading fiction altogether. Like Prose, I’m not sure I could continue to write if it required that sacrifice. But I generally take care not to read anything that’s too closely linked in any respect to the piece I’m working on.

Against the backdrop of that sort of anxiety of influence, it was instructive to read Prose on how particular works of fiction have helped her surmount obstacles in her own work:

The above passage got me thinking about the stories and novels that have had a direct impact on my work. There are numerous writers that I can cite whose work regularly inspires me, but also a handful of specific works that, on reflection, I can point to as concrete influences on specific stories of mine. Here are three of them:

Anton Chekhov’s “The Lady With the Dog”;

Delmore Schwartz’s “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities”; and,

Ali Smith’s “The Book Club.”

The interesting thing about this list is that I’m not sure that anyone else could read these stories and then read my stories and connect the dots. It’s subtle. Sometimes it’s the tone, sometimes it’s the structure, sometimes something in the content of a story sparks something unexpected for me in the manner of free association. But I can look back and remember what I learned from each of those stories that I was able to incorporate into stories of my own. This leads me to think that I ought to worry less about influence and to strive to be as receptive as possible to good writing wherever and whenever I find it.

All of this food for thought in just the first chapter of Prose’s Reading Like a Writer... I’m looking forward to the rest.

I’m only a chapter into Prose’s book and it’s already amply living up to my expectations. Here’s a passage that I identify with completely on what it means to her to read like a writer :

In the ongoing process of becoming a writer, I read and reread the authors I most loved. I read for pleasure, first, but also more analytically, conscious of style, of diction, of how sentences were formed and information was being conveyed, how the writer was structuring a plot, creating characters, employing detail and dialogue. As I wrote, I discovered that writing, like reading, was done one word at a time, one punctuation mark at a time. It required what a friend calls “putting every word on trial for its life”: changing an adjective, cutting a phrase, removing a comma, and putting the comma back in.

I read closely, word by word, sentence by sentence, pondering each deceptively minor decision the writer had made.

I also read with interest what Prose had to say about fearing the influence of other writers:

I’ve ... heard fellow writers say that they cannot read while working on a book of their own, for fear that Tolstoy or Shakespeare might influence them. I’ve always hoped they would influence me, and I wonder if I would have taken so happily to being a writer if it had meant that I couldn’t read during the years it might take to complete a novel.

I do worry about the influences that I expose myself to while I’m at the initial drafting stage of a piece of fiction. I don’t avoid reading fiction altogether. Like Prose, I’m not sure I could continue to write if it required that sacrifice. But I generally take care not to read anything that’s too closely linked in any respect to the piece I’m working on.

Against the backdrop of that sort of anxiety of influence, it was instructive to read Prose on how particular works of fiction have helped her surmount obstacles in her own work:

Occasionally, while I was teaching a reading course and simultaneously working on a novel, and when I had reached an impasse in my own work, I began to notice that whatever story I taught that week somehow helped me get past the obstacle that had been in my way. Once, for example, I was struggling with a party scene and happened to be teaching James Joyce’s “The Dead,” which taught me something about how to orchestrate the voices of the party guests into a chorus from which the principal players step forward, in turn, to take their solos.

On another occasion, I was writing a story that I knew was going to end in horrific violence, and I was having trouble getting it to sound natural and inevitable rather than forced and melodramatic. Fortunately, I was teaching the stories of Isaac Babel, whose work so often explores the nature, the causes, and the aftermath of violence. What I noticed, close-reading along with my students, was that frequently in Babel’s fiction, a moment of violence is directly preceded by a passage of intense lyricism. It’s characteristic of Babel to offer the reader a lovely glimpse of the crescent moon just before all hell breaks loose. I tried it—first the poetry, then the horror—and suddenly everything came together, the pacing seemed right, and the incident I had been struggling with appeared, at least to me, to be plausible and convincing.

The above passage got me thinking about the stories and novels that have had a direct impact on my work. There are numerous writers that I can cite whose work regularly inspires me, but also a handful of specific works that, on reflection, I can point to as concrete influences on specific stories of mine. Here are three of them:

Anton Chekhov’s “The Lady With the Dog”;

Delmore Schwartz’s “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities”; and,

Ali Smith’s “The Book Club.”

The interesting thing about this list is that I’m not sure that anyone else could read these stories and then read my stories and connect the dots. It’s subtle. Sometimes it’s the tone, sometimes it’s the structure, sometimes something in the content of a story sparks something unexpected for me in the manner of free association. But I can look back and remember what I learned from each of those stories that I was able to incorporate into stories of my own. This leads me to think that I ought to worry less about influence and to strive to be as receptive as possible to good writing wherever and whenever I find it.

All of this food for thought in just the first chapter of Prose’s Reading Like a Writer... I’m looking forward to the rest.

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

Stories in the Second Person

I’m in the middle of reading a short story collection. It’s a first collection by a young author and on the whole it seems a promising debut. There are some very strong stories in it. But there is one that has me scratching my head. It’s written in the second person and I can’t figure out why the author opted for this perspective in this story. It depicts an individual experience rich with specific detail. But rather than “she does this, she does that” or “I do this, I do that,” the author writes “you do this, you do that” and so on. What purpose does the use of the second person serve here?

It may be that despite the specificity of the experience depicted, the author is seeking to give it an air of universality. If so, I’m sceptical about the second person perspective as a device for doing so. It seems to me that an author can lay out a specific experience attributed to an individual character and in doing so convey the emotion beneath it in a way that makes the reader connect it with his or her own experience without the heavy-handed direction of addressing the character as “you.”

A related possibility is that the author is using the second person to heighten the sense of identification between reader and character. Making the main character “you” literally puts the reader in the shoes of that character. But here too I have my doubts. It seems to me that a first person story could accomplish this more effectively. A story with “I” at the centre situates the reader inside the character’s head and compels the reader to view the world through that character’s eyes. A story with “you” at the centre imposes that character’s experience on the reader from the outside. As a reader, this can make me quite belligerent. I find myself talking back to the story in childish fashion, meeting every “you did” with “no I didn’t.”

I’m not taking the position that there’s no place for the second person perspective in fiction. Indeed, one of the stories in my forthcoming collection is written in the second person. Why did I choose that perspective for that story? The “you” that the story is addressed to is not the reader but a character who features in it. It is essentially a letter from the narrator to an ex-lover. There the reader has the option of standing with the narrator who is telling the tale, or with the character to whom it is being told. Or, of course, the reader can stand outside both characters and relish the role of eavesdropper.

Another instance that I can think of where the second person can work well is in fiction in which the narrator or the author truly is addressing the reader in metafictional fashion.

Now here is the point when I start explicitly addressing this post to “you”! Do you have strong feelings one way or the other when you encounter the second person perspective in fiction? Can you offer up suggestions of novels or stories in which the second person perspective works well or of novels or stories in which you think the second person perspective fails? I’d like to grapple with this issue further and I think that a bit of research is required.

It may be that despite the specificity of the experience depicted, the author is seeking to give it an air of universality. If so, I’m sceptical about the second person perspective as a device for doing so. It seems to me that an author can lay out a specific experience attributed to an individual character and in doing so convey the emotion beneath it in a way that makes the reader connect it with his or her own experience without the heavy-handed direction of addressing the character as “you.”

A related possibility is that the author is using the second person to heighten the sense of identification between reader and character. Making the main character “you” literally puts the reader in the shoes of that character. But here too I have my doubts. It seems to me that a first person story could accomplish this more effectively. A story with “I” at the centre situates the reader inside the character’s head and compels the reader to view the world through that character’s eyes. A story with “you” at the centre imposes that character’s experience on the reader from the outside. As a reader, this can make me quite belligerent. I find myself talking back to the story in childish fashion, meeting every “you did” with “no I didn’t.”

I’m not taking the position that there’s no place for the second person perspective in fiction. Indeed, one of the stories in my forthcoming collection is written in the second person. Why did I choose that perspective for that story? The “you” that the story is addressed to is not the reader but a character who features in it. It is essentially a letter from the narrator to an ex-lover. There the reader has the option of standing with the narrator who is telling the tale, or with the character to whom it is being told. Or, of course, the reader can stand outside both characters and relish the role of eavesdropper.

Another instance that I can think of where the second person can work well is in fiction in which the narrator or the author truly is addressing the reader in metafictional fashion.

Now here is the point when I start explicitly addressing this post to “you”! Do you have strong feelings one way or the other when you encounter the second person perspective in fiction? Can you offer up suggestions of novels or stories in which the second person perspective works well or of novels or stories in which you think the second person perspective fails? I’d like to grapple with this issue further and I think that a bit of research is required.

Monday, December 11, 2006

Next Up at the Short Story Discussion Group

Next up at the short story discussion group is Franz Kafka’s "A Hunger Artist", first published shortly after his death in 1924.

The discussion begins tomorrow, Tuesday, December 12th. Participants are invited to begin posting their thoughts on the story at A Curious Singularity then. If you’re not yet a member of the short story discussion group and you would like to join, please e-mail me. Of course, anyone can contribute through the comments sections of the posts without officially joining the group.

I look forward to the discussion.

The discussion begins tomorrow, Tuesday, December 12th. Participants are invited to begin posting their thoughts on the story at A Curious Singularity then. If you’re not yet a member of the short story discussion group and you would like to join, please e-mail me. Of course, anyone can contribute through the comments sections of the posts without officially joining the group.

I look forward to the discussion.

Saturday, December 09, 2006

A.S. Byatt on Willa Cather

A.S. Byatt on Willa Cather:

To read the rest of Byatt’s article on Cather which appeared in today's Guardian, click here.

One of the virtues of her writing that I notice all the time, and find hard to describe, is the distance at which she stands from her text. Part of what I mean by this is contained in the fact that more than any other novelist she sees her people's lives as whole and finished - they feel stress and passion, they discover and lose, but they are bounded by birth and death, by nothing and nothing, and they move between the two, adjusting their consciousnesses as they go. The writer always sees the people's lives whole and complete, wherever the story is along their line.

To read the rest of Byatt’s article on Cather which appeared in today's Guardian, click here.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Consulting a Dictionary

I’ve been thinking about dictionaries. It was yesterday’s vocabulary quiz that got me on this track. How is it, I wondered, that I couldn’t produce a definition of quixotic or phlegmatic with certainty despite being familiar with both words?

I have a dictionary of which I’m rather fond (The Canadian Oxford Dictionary), and I consult it with some regularity. But I’ve realized that while I consult it when I’m writing, I almost never do so when I’m reading. I look up words that I already know to check the proper spelling. Or I look up words that I think I know to erase any doubt about whether I’m using them properly. Only very rarely do I pause in the middle of a book that I’m reading to look up an unfamiliar word and find out what it means. If the unfamiliar word is so crucial that I can’t make sense of the passage in which it appears without a precise definition, I will stir myself to look it up. Most of the time, however, I just guess what the word means from the context and continue on. Eventually, after repeated encounters, my initial guess develops into a solid conviction. I don’t bother to test that conviction until I opt to use the word in print myself. This method seems to work. Nevertheless, on reflection it strikes me as a rather sloppy way to build a vocabulary. Perhaps it’s time I changed my ways.

Do you own a dictionary? Have you eschewed paper and ink dictionaries in favour of virtual ones? When do you consult a dictionary, and for what purpose?

I have a dictionary of which I’m rather fond (The Canadian Oxford Dictionary), and I consult it with some regularity. But I’ve realized that while I consult it when I’m writing, I almost never do so when I’m reading. I look up words that I already know to check the proper spelling. Or I look up words that I think I know to erase any doubt about whether I’m using them properly. Only very rarely do I pause in the middle of a book that I’m reading to look up an unfamiliar word and find out what it means. If the unfamiliar word is so crucial that I can’t make sense of the passage in which it appears without a precise definition, I will stir myself to look it up. Most of the time, however, I just guess what the word means from the context and continue on. Eventually, after repeated encounters, my initial guess develops into a solid conviction. I don’t bother to test that conviction until I opt to use the word in print myself. This method seems to work. Nevertheless, on reflection it strikes me as a rather sloppy way to build a vocabulary. Perhaps it’s time I changed my ways.

Do you own a dictionary? Have you eschewed paper and ink dictionaries in favour of virtual ones? When do you consult a dictionary, and for what purpose?

Monday, December 04, 2006

How's Your Vocabulary Quiz

This is a fun one. The two words that I paused over were quixotic and phlegmatic, but it seems that I made the right call on both.

Thanks to Frank Wilson at Books, Inq. for the link.

| Your Vocabulary Score: A+ |

Congratulations on your multifarious vocabulary! You must be quite an erudite person. |

Thanks to Frank Wilson at Books, Inq. for the link.

Fictitious Photos

Sharon Harris has posted some photos that she took at the most recent Fictitious Reading on her i love you galleries site. Click here to see them.

Sunday, December 03, 2006

Cam's Poetry Meme

I read a lot of poetry but seldom write about it here. Cam’s poetry meme offers me a welcome opportunity to begin to rectify that situation. Here are my responses to her prompts.

1. The first poem I remember reading/hearing/reacting to was:

The earliest encounter with poetry that I can recall was having my mom read to me from Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses. I still have the puffin paperback edition of the book from which she read to me and if pressed I can still recite the odd verse from it. The one that I remember most vividly is “The Lamplighter” and it was a great treat earlier this year to visit RLS’s childhood home at 17 Heriot Row in Edinburgh and see “the lamp before the door” that is said to have inspired the poem.

2. I was forced to memorize (name of poem) in school and…

I was never forced to memorize a poem in school. However, I did choose to do so for a public speaking competition when I was in the second grade. I have no idea what prompted me to do this. I was painfully shy to the extent that I would forgo candy rather than face the terror of interacting with a store clerk. Yet somehow I screwed up my courage to take to the stage in the school auditorium and recite a poem. The poem I recited was “Father” by Edgar Albert Guest. My grandpa, despite having had to quit school and go to work at the age of twelve, could recite many poems from memory. “Father” was one of his favourites and that’s why I chose it. I won an honourable mention in the competition and no doubt I wrote my grandpa immediately afterward to tell him so. The poem still makes me chuckle.

3. I read/don't read poetry because…

I read poetry because it gives me enormous pleasure and because it challenges me—sometimes one or the other, but if it’s a very good poem it will do both at once. I’m particularly likely to read poetry when I’m writing fiction. Reading fiction while I’m writing it disrupts or distracts me, whereas reading poetry while writing fiction inspires me and sharpens my focus somehow.

4. A poem I'm likely to think about when asked about a favorite poem is:

Not surprisingly, my favourites shift over time. If you’d asked me what my favourite poem was when I was in high school, without hesitation I would have said William Butler Yeats’ "Aedh Wishes For the Cloths of Heaven”. In my twenties, I might have said Margaret Atwood’s “You Fit into Me” or e.e. cummings’ “in Just-”. A more recent favourite is Delmore Schwartz’s extraordinary “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me”.

5. I write/don't write poetry, but…

I used to write poetry but, alas, my poems weren’t very good. I didn’t find my form until I began writing fiction. But I certainly don’t consider the time I spent trying to write poetry to have been wasted. My attempts made me a better reader of poetry and a better writer of fiction.

6. My experience with reading poetry differs from my experience with reading other types of literature…

My reading of poetry is more erratic than is my reading of fiction. I’m more likely to dip in and out of a poetry book, to stretch my reading of it out over a very long period of time, or perhaps never to finish it at all. On the upside (for the poets out there), this means that while I often borrow the fiction that I read from the library, I almost always opt to buy poetry books because I know I'll get a lot of reading out of them.

7. I find poetry… indispensable.

8. The last time I heard poetry…

I can’t remember precisely when the last time I heard poetry was. This is not because it’s a rare occurrence but because it’s a frequent one. Toronto is awash in poetry reading series and consequently opportunities to hear excellent poets read from their work abound. Particularly memorable readings from the past year include Lisa Robertson’s reading from her excellent collection The Men at the Test Reading Series, and Jen Currin's reading from her debut collection The Sleep of Four Cities at the last dig launch. I highly recommend both of their books.

9. I think poetry is like… nothing else. At its best it can’t be paraphrased. It conveys something that can’t be conveyed in any other form. Poetry is poetry.

This meme has been floating around the litblogosphere for a while now so I’m not sure who is left to be tagged. I’d like to hear from anyone who hasn’t yet weighed in with responses to Cam’s excellent questions. I’d be particularly interested to hear from some of my poet friends if they fancy participating. Jen? Stuart? Rob?

1. The first poem I remember reading/hearing/reacting to was:

The earliest encounter with poetry that I can recall was having my mom read to me from Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses. I still have the puffin paperback edition of the book from which she read to me and if pressed I can still recite the odd verse from it. The one that I remember most vividly is “The Lamplighter” and it was a great treat earlier this year to visit RLS’s childhood home at 17 Heriot Row in Edinburgh and see “the lamp before the door” that is said to have inspired the poem.

2. I was forced to memorize (name of poem) in school and…

I was never forced to memorize a poem in school. However, I did choose to do so for a public speaking competition when I was in the second grade. I have no idea what prompted me to do this. I was painfully shy to the extent that I would forgo candy rather than face the terror of interacting with a store clerk. Yet somehow I screwed up my courage to take to the stage in the school auditorium and recite a poem. The poem I recited was “Father” by Edgar Albert Guest. My grandpa, despite having had to quit school and go to work at the age of twelve, could recite many poems from memory. “Father” was one of his favourites and that’s why I chose it. I won an honourable mention in the competition and no doubt I wrote my grandpa immediately afterward to tell him so. The poem still makes me chuckle.

3. I read/don't read poetry because…

I read poetry because it gives me enormous pleasure and because it challenges me—sometimes one or the other, but if it’s a very good poem it will do both at once. I’m particularly likely to read poetry when I’m writing fiction. Reading fiction while I’m writing it disrupts or distracts me, whereas reading poetry while writing fiction inspires me and sharpens my focus somehow.

4. A poem I'm likely to think about when asked about a favorite poem is:

Not surprisingly, my favourites shift over time. If you’d asked me what my favourite poem was when I was in high school, without hesitation I would have said William Butler Yeats’ "Aedh Wishes For the Cloths of Heaven”. In my twenties, I might have said Margaret Atwood’s “You Fit into Me” or e.e. cummings’ “in Just-”. A more recent favourite is Delmore Schwartz’s extraordinary “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me”.

5. I write/don't write poetry, but…

I used to write poetry but, alas, my poems weren’t very good. I didn’t find my form until I began writing fiction. But I certainly don’t consider the time I spent trying to write poetry to have been wasted. My attempts made me a better reader of poetry and a better writer of fiction.

6. My experience with reading poetry differs from my experience with reading other types of literature…

My reading of poetry is more erratic than is my reading of fiction. I’m more likely to dip in and out of a poetry book, to stretch my reading of it out over a very long period of time, or perhaps never to finish it at all. On the upside (for the poets out there), this means that while I often borrow the fiction that I read from the library, I almost always opt to buy poetry books because I know I'll get a lot of reading out of them.

7. I find poetry… indispensable.

8. The last time I heard poetry…

I can’t remember precisely when the last time I heard poetry was. This is not because it’s a rare occurrence but because it’s a frequent one. Toronto is awash in poetry reading series and consequently opportunities to hear excellent poets read from their work abound. Particularly memorable readings from the past year include Lisa Robertson’s reading from her excellent collection The Men at the Test Reading Series, and Jen Currin's reading from her debut collection The Sleep of Four Cities at the last dig launch. I highly recommend both of their books.

9. I think poetry is like… nothing else. At its best it can’t be paraphrased. It conveys something that can’t be conveyed in any other form. Poetry is poetry.

This meme has been floating around the litblogosphere for a while now so I’m not sure who is left to be tagged. I’d like to hear from anyone who hasn’t yet weighed in with responses to Cam’s excellent questions. I’d be particularly interested to hear from some of my poet friends if they fancy participating. Jen? Stuart? Rob?

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Nick Mount on a Literature’s Beginnings

Nick Mount on a literature’s beginnings:

From Nick Mount, When Canadian Literature Moved to New York (2005).

All literatures have three beginnings. A literature’s first beginning is the moment of its emergence, often in quasi- or extra-literary forms: oral celebrations of gods and heroes, chronicles of distant legend or current crop conditions, narratives of exploration and travel (or captivity and slavery), and so on. Its second beginning is marked by its writers’ self-conscious recognition of themselves as writers (rather than, say, explorers who write), and of their membership in or connection to a community of others who share that recognition. Much more so than the first, this second beginning depends upon the existence of those who will produce, distribute, and consume the literature — conventionally, the publisher, the bookseller, and the reader, though it hasn’t always been so, and occasionally modern communities of writers have found substitutes for one or more of these functions. Because of its dependence upon a market, a literature’s second beginning is most clearly announced by the professionalization of its writers, by the moment at which they begin to earn their living from, or mostly from, their writing. Finally, a literature undergoes its third beginning when it receives critical or institutional recognition as a literature, that is, as a discrete body of writing, with its own history and its own set of works and characteristics. In its actual life any literature is far too internally disparate and too interwoven with other literatures to admit such definition. When we say ‘a literature,’ what we really mean is an object that exists only in perception, an object whose birth was simultaneous with its recognition and that survives only in restatements of that recognition…

From Nick Mount, When Canadian Literature Moved to New York (2005).

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Fictitious Reading Series 8

The eighth instalment of The Fictitious Reading Series will take place on Sunday, November 26th at 7:30 pm in the gallery space above This Ain’t the Rosedale Library (483 Church Street, Toronto). This month’s featured writers are John Degen and Jennifer LoveGrove. The evening will include readings by John and Jennifer, as well as an informal onstage interview with them. Stuart Ross will host, and I’ll conduct the interview.

John Degen is the author of two books of poetry, Animal Life in Bucharest and Killing Things. His first novel, The Uninvited Guest, was recently published by Nightwood Editions. The first chapter is available to be read online at the Globe and Mail. John is the former editor/publisher of ink magazine, and he writes political commentary for This Magazine. He lives in Toronto where he is the executive director of the Professional Writers Association of Canada.

John Degen is the author of two books of poetry, Animal Life in Bucharest and Killing Things. His first novel, The Uninvited Guest, was recently published by Nightwood Editions. The first chapter is available to be read online at the Globe and Mail. John is the former editor/publisher of ink magazine, and he writes political commentary for This Magazine. He lives in Toronto where he is the executive director of the Professional Writers Association of Canada.

Jennifer LoveGrove is the author of two books of poetry, The Dagger Between Her Teeth and I Should Never Have Fired the Sentinel. Her fiction has been published in Taddle Creek. She is currently at work on a novel with the working title Watch How We Walk. Jennifer lives in Toronto where she is the editor/publisher of wayward armadillo press and of the literary zine dig.

Jennifer LoveGrove is the author of two books of poetry, The Dagger Between Her Teeth and I Should Never Have Fired the Sentinel. Her fiction has been published in Taddle Creek. She is currently at work on a novel with the working title Watch How We Walk. Jennifer lives in Toronto where she is the editor/publisher of wayward armadillo press and of the literary zine dig.

For more information on the series, see the Fictitious website.

John Degen is the author of two books of poetry, Animal Life in Bucharest and Killing Things. His first novel, The Uninvited Guest, was recently published by Nightwood Editions. The first chapter is available to be read online at the Globe and Mail. John is the former editor/publisher of ink magazine, and he writes political commentary for This Magazine. He lives in Toronto where he is the executive director of the Professional Writers Association of Canada.

John Degen is the author of two books of poetry, Animal Life in Bucharest and Killing Things. His first novel, The Uninvited Guest, was recently published by Nightwood Editions. The first chapter is available to be read online at the Globe and Mail. John is the former editor/publisher of ink magazine, and he writes political commentary for This Magazine. He lives in Toronto where he is the executive director of the Professional Writers Association of Canada. Jennifer LoveGrove is the author of two books of poetry, The Dagger Between Her Teeth and I Should Never Have Fired the Sentinel. Her fiction has been published in Taddle Creek. She is currently at work on a novel with the working title Watch How We Walk. Jennifer lives in Toronto where she is the editor/publisher of wayward armadillo press and of the literary zine dig.

Jennifer LoveGrove is the author of two books of poetry, The Dagger Between Her Teeth and I Should Never Have Fired the Sentinel. Her fiction has been published in Taddle Creek. She is currently at work on a novel with the working title Watch How We Walk. Jennifer lives in Toronto where she is the editor/publisher of wayward armadillo press and of the literary zine dig.For more information on the series, see the Fictitious website.

Saturday, November 18, 2006

A Scattered Post on a Scattered Day

Nowhere on my voluminous "To Do" list was there an imperative to re-read Betsy and the Great World, my favourite instalment in Maud Hart Lovelace's Betsy-Tacy series. But I spent part of today doing just that. Nothing calms me in times of stress as effectively as revisiting a book that is essentially an old friend. Today, Betsy and the Great World did the trick.

For those of you not initiated into the cult of Betsy-Tacy, I offer up an excerpt from the first chapter which nicely sets up the rest of the book. As far as background goes, this particular scene takes place in the summer of 1913, Julia is Betsy’s older sister, Margaret her younger sister, and Tacy her best friend.

"Don’t think," Mr. Ray continued, "that Mamma and I haven’t seen which way the wind was blowing. You haven’t been happy, Betsy, and we’ve known it."

Betsy didn’t speak.

"You’re going to be a writer," he proceeded thoughtfully. "No doubt about that! You’ve been writing all your life. And you’ve worked harder this summer at that story you’re writing than you’ve worked for all your professors put together. What’s the name of it anyway?"

"'Emma Middleton Cuts Cross Country,'" Betsy replied. "It's about a little dressmaker, like the one who made my Junior Ball dress. She gets disgusted with everything and walks out and makes a new start."

"Sounds good," said Mr. Ray, nodding sagely, although he never read stories, except Betsy’s. "You certainly write like a whiz. Do you remember the letter Dr. Sanford wrote you about your story in the college magazine?"

Betsy nodded, moist-eyed.

"I was very proud of that letter," Mr. Ray said, which made her tears spill over for it seemed to her that she had given him very little reason to be proud of her lately. He put down his cigar.

"You're going to be a writer," he repeated, "and you need more education. That’s plain. But college isn’t the only place to get an education. I have a 'snoggestion.'" That was what Mr. Ray always called a particularly good suggestion. "I've sounded Mamma out and she approves. How would you like a year abroad?"

"But, Papa!" Betsy had thrown her arms around him, frankly crying now. "What a glo-glo-glorious snoggestion! I've always planned to go. But I never thought of you sending me. I thought I’d earn the money myself some day."

"Oh, I don’t think it would cost so much more than a year at the U!" said Mr. Ray. "You'd have to go in a modest way, of course. But Julia had two trips abroad. You’re entitled to one, too. Maybe when Margaret goes, Mamma and I will go along."

"Would I ... would I go to school over there?"

"You don't seem to be getting what you need out of a school. But judging by our experience with Julia, you learn a lot just from traveling in Europe ... seeing the art galleries, learning the languages and all that stuff. You could go on a guided tour like Julia did."

"No, Papa!" Betsy knelt beside him, her hands on his knee. "Guided tours are all right for some people, but not for a writer. I ought to stay in just two or three places. Really live in them, learn them. Then if I want to mention London, for example, in a story, I would know the names of the streets and how they run and the buildings and the atmosphere of the city. I could move a character around in London just as though it were Minneapolis. I don’t want to hurry from place to place with a party the way Julia did."

Her father looked perplexed.

"But it doesn’t seem safe, Betsy. You're only twenty-one. You know how much confidence Mamma and I have in you, but we wouldn't want you living in those big foreign cities all alone."

"Maybe we could pick out cities where I know someone ... or you do, or Julia."

"Maybe. I’ll talk it over with your mother."

So Betsy dashed off to Tacy’s apartment and they talked, talked about the wonderful trip.

"I’m just going to travel around like Paragot," Betsy said, referring to a character in William J. Locke’s novel, The Beloved Vagabond, a favourite with both of them.

And off she goes, setting forth from Boston on the S.S. Columbic in January 1914 and spending time in Munich, Venice, Paris, and London until the start of WWI cuts her travels short.

I’ve been meaning to read The Beloved Vagabond ever since I saw it referenced in Betsy and the Great World, but decades on I still haven’t gotten round to it. One book often leads me to another in my non-fiction reading; this is particularly true of literary biographies. But, though I often intend to, I can’t think of too many instances when I’ve taken up the book recommendations of fictional characters. Have you ever read a book simply because you read a reference to it in another book? Which ones?

I’m off to put a copy of The Beloved Vagabond on hold at the library. I’ll keep you posted as to how it measures up after a couple of decades of anticipation...

[Illustrations from Betsy and the Great World are by Vera Neville.]

Friday, November 17, 2006

Samuel Delany on Doubt and the Writing Process

Samuel Delany on doubt and the writing process:

(From Samuel R. Delany, “Of Doubts and Dreams” in About Writing: 7 essays, 4 letters, and 5 interviews (2006).)

I have sometimes thought that my compulsion to revise as I go is a flaw in my writing process, that I ought to train myself to draft now and revise later and thereby become more prolific. Delany’s marvellous essay on doubt as a crucial part of the writing process suggests otherwise. I’m really struck by his idea that revising as you go doesn’t only change what you’ve already written; it changes what you will write next, and changes it for the better. Rather than slowing you down, it takes you in a new direction. Perhaps it’s time to put more faith in my doubt…

A unique process begins when the writer lowers the pen to put words on paper—or taps out letters on to the page with typewriter keys. Certainly writers think about and plan stories beforehand; and certainly, after writing a few stories, you may plan them or think about them in a more complex way. But even this increased complexity is likely to grow out of the process of which I’m speaking. The fact is almost everyone thinks about stories. Many even get to the point of planning them. But the place where the writer’s experience differs from everyone else’s is during the writing process itself. What makes this process unique has directly to do with the doubting.

You picture the beginning of a story. (Anyone can do that.) You try to describe it. (And anyone can try.) Your mind offers up a word, or three, or a dozen. (It’s not much different from what happens when you write a friend in a letter what you did yesterday morning.) You write the words down, the first, the second, the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh—suddenly you doubt.

You sense clutter, or thinness, or cliché.

You are now on the verge of a process that happens only in the actual writing of a text.

If the word you doubted is among those already written down, you can cross it out. If it’s among the words you’re about to write, you can say to yourself, “No, not that one,” and either go on without it, or wait for some alternative to come. The act of refusing to put down words, or crossing out words already down, while you concentrate on the vision you are writing about, makes new words come. What’s more, when you refuse language your mind offers up, something happens to the next batch offered. The words are not the same ones that would have come if you hadn’t doubted.

The differences will probably have little or nothing to do with your plot, or the overall story shape—though they might. There will probably be much to reject among the new batch too. But making these changes the moment they are perceived keeps the tale curving inward toward its own energy. When you make the corrections at the time, the next words that come up will be richer—richer both in things to accept and to reject.

(From Samuel R. Delany, “Of Doubts and Dreams” in About Writing: 7 essays, 4 letters, and 5 interviews (2006).)

I have sometimes thought that my compulsion to revise as I go is a flaw in my writing process, that I ought to train myself to draft now and revise later and thereby become more prolific. Delany’s marvellous essay on doubt as a crucial part of the writing process suggests otherwise. I’m really struck by his idea that revising as you go doesn’t only change what you’ve already written; it changes what you will write next, and changes it for the better. Rather than slowing you down, it takes you in a new direction. Perhaps it’s time to put more faith in my doubt…

Monday, November 13, 2006

Next Up at the Short Story Discussion Group

Next up at the short story discussion group is Katherine Mansfield’s "At the Bay", a story set in her native New Zealand that was first published in 1921.

The discussion begins tomorrow, Tuesday, November 14th. Participants are invited to begin posting their thoughts on the story at A Curious Singularity then. If you’re not yet a member of the short story discussion group and you would like to join, please e-mail me. Of course, anyone can contribute through the comments sections of the posts without officially joining the group.

I look forward to the discussion.

The discussion begins tomorrow, Tuesday, November 14th. Participants are invited to begin posting their thoughts on the story at A Curious Singularity then. If you’re not yet a member of the short story discussion group and you would like to join, please e-mail me. Of course, anyone can contribute through the comments sections of the posts without officially joining the group.

I look forward to the discussion.

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Early Reading Meme

I’ve decided to have a go at creating a meme. I’ve been re-reading some childhood favourites lately and thinking a lot about the process of becoming a reader, so I’m taking early reading experiences as my subject. Herewith are my questions and my answers:

1. How old were you when you learned to read and who taught you?

I learned to read when I was four. I was then in the habit of following my older brother everywhere and copying everything that he did. He was in first grade and reading, so I pestered my mom until she taught me how. No doubt much to my brother’s relief, I spent a lot less time following him around thereafter. I was too busy reading.

2. Did you own any books as a child? If so, what’s the first one that you remember owning? If not, do you recall any of the first titles that you borrowed from the library?

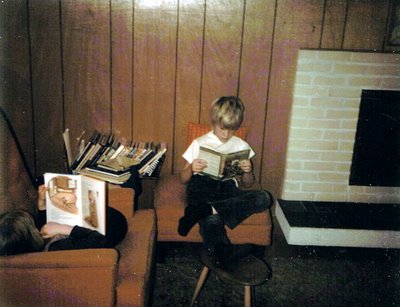

There was a tattered copy of Grimm’s fairytales with a soft yellow cover from which my mom read to us when we were very young. That was likely the first one. But it was quickly followed by the acquisition of a whole set of hardcover “I Can Read” books which ranged from very basic read-aloud books to beginning chapter books. In the former category, my particular favourites were Hop on Pop, One Fish Two Fish, Are You My Mother?, and Put Me in the Zoo. In the latter category, the one I liked best was an abridged version of Heidi. In the photo posted above, that’s me as a child curled up in the armchair reading Heidi. I can’t make out the title of the book my brother is reading. The Grimm’s fairytale book has since disappeared. But I believe that all those “I Can Read” books are now part of my nieces’ collection.

Early favourite check-outs from the library were Munro Leaf’s Wee Gillis and M. Lindman’s books about Swedish triplets Snip, Snap and Snurr, and Flicka, Ricka, and Dicka.

3. What’s the first book that you bought with your own money?

The first books that I recall buying with my own money were Enid Blyton’s “St. Clare’s” and “Malory Towers” boarding school series. I was ten-years-old and we were on a caravan trip in the north of Scotland. I’d read a few books from each series at my cousin’s before we set off, and I was elated to find a complete set of both in a small shop about a half-hour walk from the campground where we were staying. I had saved up several weeks of allowance money and I promptly spent the lot on them. I remember my brother making fun of me when I realized that the shop owner had given me too much change and I insisted on walking all the way back to the store to return the excess. I was quite sure that the boarding school code of honour embodied in the books required no less of me.

4. Were you a re-reader as a child? If so, which book did you re-read most often?

I was a compulsive re-reader as a child which makes it a bit difficult to identify which of my many re-reads that I re-read most often. I think it’s a toss up between the high school books in Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy series, and L.M. Montgomery’s Anne and Emily books.

5. What’s the first adult book that captured your interest and how old were you when you read it?

I read Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind just after I turned twelve and was completely captivated by it. I lugged an enormous hard cover library copy of it with me everywhere all summer: to the pool, to summer camp, on a weekend trip to a friend’s cabin. It’s a wonder it made it back to the library in one piece.

6. Are there children’s books that you passed by as a child that you have learned to love as an adult? Which ones?

As a child I read the odd book with a magical element to it: books by E. Nesbit, P.L. Travers, and L. Frank Baum. But I generally preferred realistic books and I had the idea fixed in my head that I didn’t like to read fantasy. Although I loved series books, I skipped right past Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles and Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising series on the library shelf without so much as reading the full jacket copy descriptions. Since Tolkien is a particular favourite of my dad’s and my brother’s, I tried several times to read The Hobbit. But I found Gollum repellent and I never made it beyond his first appearance in the book. I never even attempted The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

It was Harry Potter that turned this around for me. A couple of years ago, several participants in a children’s literature list-serv of which I’m a member raved so eloquently about J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books that I decided to find out what all the fuss was about. Four books in the series had already been published by then, and I was so taken with the first that I promptly went out and bought the set and read the rest in rapid succession. Somehow, this experience broke through my mental block about the whole fantasy genre. Thereafter I read with pleasure all the classic fantasy series that I’d spurned as a child including the Prydain Chronicles, the Dark is Rising series, and Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogy. I’ve since gone on to explore several marvellous contemporary children’s fantasy books by the likes of Phillip Pullman, Diana Wynne Jones, and Terry Pratchett.

The Harry Potter books have been credited with getting reluctant child readers to read. I can testify to the fact that they also got this avid adult reader but reluctant fantasy reader to embrace a genre the charms of which had previously escaped me.

Consider yourselves tagged! I want to hear all about the early reading that set you on the path to becoming the reader that you are today.

Update: Lots of bloggers are chiming in on this one with some very interesting responses to my questions. Here are links to those that I've come across so far:

a high and hidden place

A Work in Progress

Around the World in 100 books

Big A little a

BookLust

Cam's Commentary

Critical Mass

Dabbling Dilettante

Dumb Ox Academy

everywakinghour

FeatherBee

Gray's Academy

Journey Woman

Lady Strathconn's Journal

Lotus Reads

Mommy Brain

My Novel on Toast

Nom de Plume

Of Books and Bicycles

Original Content

Out of a Stormy Sleep

pages turned

Poohsticks

Reading Log Blog

satyridae

Semicolon

So Many Books

Stephen Lang

Terry Teachout

The Bayer Family Blog

The Books of My Numberless Dreams

The Golden Road to Samarqand

The Hobgoblin of Little Minds

The Library Ladder

The Literate Kitten

The Pickards

The Public, The Private, and Everything In Between

Tiger by the Tale

VWSISTA

White Thoughts No-One Sees

Wormbook

Written Wyrdd

Friday, November 10, 2006

Review in the Women's Post

My review of Caroline Adderson’s new book Pleased to Meet You appears today in the Women’s Post. It’s an excellent short story collection which I highly recommend. To read my review online, click here.

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Projecting Criticism

I’m a hypercritical reader these days. I’m looking at everything with an eye to revision, even when I’ve moved on from my own work to something else. I’ve noted as well that my sharpest criticism is provoked by those facets of the fiction of other writers that reflect the flaws in my own work. I haven’t yet sorted out whether it’s a matter of already being aware of those flaws in my work and thus being particularly alert to their presence in anything else that I read. Or if it’s a matter of being able to identify those flaws elsewhere first as a step along the way toward acknowledging their presence in my work. Either way, although for the moment it has rendered my bedtime reading much less relaxing, this acute form of “reading like a writer” seems to be working for me at this stage in the process.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Paul Auster on the Novel as Meeting Place

Paul Auster on the novel as meeting place:

For the rest of the speech from which this excerpt comes, click here.

[W]hen it comes to the state of the novel, to the future of the novel, I feel rather optimistic. Numbers don't count where books are concerned, for there is only one reader, each and every time only one reader. That explains the particular power of the novel and why, in my opinion, it will never die as a form. Every novel is an equal collaboration between the writer and the reader and it is the only place in the world where two strangers can meet on terms of absolute intimacy.

For the rest of the speech from which this excerpt comes, click here.

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Pooh Corner Turns Forty

I’ve written here before about my fond memories of the library that I frequented as a child. I very vividly recall attending story hour in “Pooh Corner,” a dim, cave-like room that one entered through a door in what appeared to be the trunk of a tree. Well, I’ve just learned that it’s the 40th birthday of Pooh Corner and that I could have attended a variety of homecoming events there today had I been within travelling distance of my hometown. I’m sad to have missed it, but tickled to discover the existence of a Pooh Corner blog which occasionally features old photos of that marvellous place just as I remember it.

For a few more photos, click here.

Friday, November 03, 2006

Yet Another Challenge

I know, I know. I just signed on for Kailana’s November challenge, and I haven’t yet reported in on my R.I.P. Autumn Challenge reads. But there’s another challenge in the works at Overdue Books that sounds tailor-made for me. Dubbed the From the Stacks Winter Challenge, the goal is to read "5 books that we have already purchased, have been meaning to get to, [...] and haven't read before. No going out and buying new books. No getting sidetracked by the lure of the holiday bookstore displays." The time frame is from November 1st to January 30th.

I know, I know. I just signed on for Kailana’s November challenge, and I haven’t yet reported in on my R.I.P. Autumn Challenge reads. But there’s another challenge in the works at Overdue Books that sounds tailor-made for me. Dubbed the From the Stacks Winter Challenge, the goal is to read "5 books that we have already purchased, have been meaning to get to, [...] and haven't read before. No going out and buying new books. No getting sidetracked by the lure of the holiday bookstore displays." The time frame is from November 1st to January 30th. Some of you may remember that one of my resolutions for this year was to read more books from my own collection. I’ve tallied up the numbers and it appears that I’ve made good on it. Of the 109 books I read in 2005, a scant 14 were books from my own collection. Whereas of the 82 books I’ve read so far in 2006, 28 were from my own collection. Upon closer examination, however, I must concede that I’ve adhered to the letter but not the spirit of the resolution. You see 16 of those 28 were new books that I’ve acquired since making the resolution. And of the 12 that remain, 11 were re-reads of old favourites. So only one of the 28 was actually among the tomes languishing unread on my shelves to which I resolved to turn my attention back in January.

The upshot is that I feel honour-bound to join the From the Stacks Winter Challenge, and to revise the terms slightly so as to serve the original goal of my resolution. That is, in addition to being books I already own that I’ve been meaning to but haven’t yet read, my five selections will have to be books that I acquired before 2006. Precisely which five books? I’ll have to think on that a bit more before committing myself, but I expect that the final five will include these three: Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, and Katherine Mansfield’s Letters and Journals.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Revising in My Sleep

I’ve been having a lot of dreams about revising lately. Not stress dreams of the sort from which I wake exhausted feeling as if I’ve worked all night yet accomplished nothing. Rather, dreams from which I wake feeling sharp and invigorated, as though taking time out to sleep hasn’t slowed my momentum in the slightest. Not that I emerge from them with actual fixes in mind for the stories I’m wrestling with in my waking hours. Nevertheless I take the dreams as a reassuring sign that my subconscious is working for me in the endeavour to get my manuscript into final form. The end is in sight.

Monday, October 30, 2006

November Reading Challenge

There’s only one day left in October and I’ve still got one scary book left to read to complete Carl V.’s R.I.P. Autumn Reading Challenge. What better time to make grand plans for next month…

Remembrance Day falls on November 11th in Canada and in honour of that Kailana has proposed a November Challenge: to read at least three books over the course of the month set during World War I or II. I’ve scanned my TBR shelves and found several books that fit the bill by virtue of their setting or subject:

Restless by William Boyd;

A Richer Dust: Family, Memory, and the Second World War

by Robert Calder;

Love, Sex and War: 1939-1945 by John Costello;

I Was a Child of Holocaust Survivors by Bernice Eisenstein;

Brass Buttons and Silver Horseshoes: Stories from Canada’s

British War Brides by Linda Granfield;

The Other Side of the Bridge by Mary Lawson;

The Friends of Meager Fortune by David Adams Richards;

Villa Air-Bel: World War II, Escape, and a House in Marseille

by Rosemary Sullivan;

The Night Watch by Sarah Waters; and,

The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume I: 1915-1919.